Strange TV

Strange Film Reviews

Sunday, March 23, 2025

REVIEWED: Bob Dylan Gets the Hollywood Treatment in A Complete Unknown

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

REVIEWED: Luca Guadagnino's Adaptation of William Burroughs' early novella Queer.

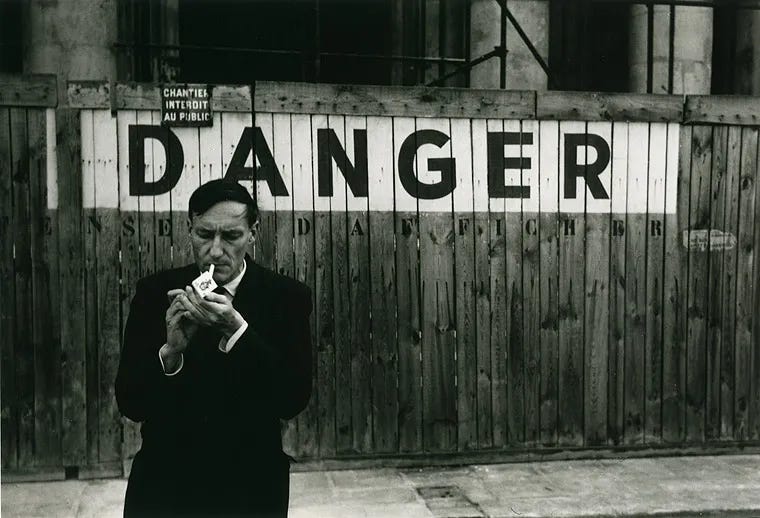

William Burroughs – A man who shot his wife, battled drug addiction throughout his life, cut off his little finger on a Van Gogh kick, and found himself in trouble with the law in pretty much every country he ever lived in, and, as Luca Guadagnino’s recent film reveals, was definitely Queer.

Before shooting began, expectations were high. James Bond legend Daniel Craig plays the author during his troubled time as a Mexican expat seeking companionship and direction. During this period of his life Burroughs became perhaps the first American outside of funded research college programs to venture into the jungle in search of Ayahuasca. Nowadays college kids do it on their gap year.

Burroughs bounces from alcohol to heroin addiction with all the free will of a Rizla paper in a cyclone, while being drawn, moth-like, to Allerton, a young American expat student, played by Drew Starkey, who frequents the local Ship Ahoy bar.

Burroughs has always been an interesting character to dramatize. Movies such as Beat, Kill Your Darlings, and the adaptation of Naked Lunch have, perhaps lazily, chosen to base their characters on the cold, dry, nasal-spoken persona Burroughs offered to the media. Remember, Burroughs was no slouch when it came to the media. His uncle, Poison Ivy Lee, was a PR man who handled Hitler’s American publicity campaign – “We don’t report the news, we write it,” Ivy would yell to his nephew while scoping a bird and pulling the trigger on their weekly duck-hunting expeditions. A seven-year-old Burroughs knew from an early age that the world was run by deep, inherent corruption. Old whiskey-drinking cigar-smoking card players made rich through striking oil and getting cured or inheriting it from long lines of dynastic wealth.

Guadagnino decides to go deeper than the gun-wielding anarchist of popular mythology, deeper than the inner causmanault on voyages of drug-addled self-discovery. This new film brings Burroughs to an entirely new generation, precisely because of the sensitive portrayal of his personal life, and at a time when they need him most.

Can we really celebrate a society that tolerated a man who shot his wife, bribed the judge, and sailed to Morocco to live among thieves, drug addicts, artists, and magicians? Of course we can. And here he sits on the bookshelf, next to Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Bulgakov’s The Master and the Margarita. Deep beneath the turmoil and the chaos of the man and the writing, there was something profoundly honest and human in the writer. Burroughs believed in the Johnstone approach to life – mind one’s own business and help out others when needed.

Like drug addiction begins for many youths, my own introduction to Burroughs started as a dare. Warned by close friends not to touch Naked Lunch as a kid, I was naturally curious but wisely began by dipping into the less murky, literal pools first. Junky is straightforward, hard-boiled prose typical of the pulp press that originally published it—think Dashiell Hammett or Chandler, with simple declarative sentences: "Junkies wore hats—if they had hats."

Next up, the beautifully bizarre world of Cities of the Red Night—his masterpiece. A dreamscape world of pirates, gumshoe detectives, aliens, and foreign lands. Convinced this shady literary character was a genius, the interviews, letters, and folklore did little to throw me off the trajectory of his career. There was, of course, the problematic cut-up period, where many of us lost the thread, but his work during that time on tape recordings and film makes up for the lack of narrative form.

By the time I read Queer, I was familiar with the landscape. The film is close to the novella, lifting some of the best lines for the screenplay – “Get off of your ass, or what’s left of it after five years in the navy” springs to mind, or the part about the boyfriend cleaning out the place rather than cleaning up.

The film looks beautiful. Thai cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, best known for his work with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, frames scenes both expansive and restrictive, evoking the spirit of the book. The interior shots of the bar and the apartments are both authentic and realistic. The soundtrack, composed by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, adds to the film – Nirvana’s Come as You Are plays as locals crowd around a symbolic street cockfight. Lee notices Allerton, the hunt is on.

Could we have done without the erotic love scenes? Possibly yes. Nobody really wants to see their literary hero blow a dude in a shabby apartment room, but if Luca Guadagnino felt it essential, then blown he must be. The two lead roles play cat and mouse (Allerton isn’t gay but accepts Lee as a friend) before flying to South America. Here Burroughs suffers the unpleasant flu-like symptoms of opiate withdrawal before hacking through the jungle and encountering a symbolic anaconda at the entrance to the hut of an old botanist doctor. The crazed herbalist is played brilliantly by Lesley Manville swinging her handgun, again, symbolic-like, mid conversation.

Here, in the jungle, the film switches source material from Queer (the book itself ends with the idea to find the telepathic drug) to The Yage Letters, a book of correspondence from Burroughs’s time in the Amazonian bush. Luca and Sayombhu attempt the impossible at this point by representing, in images and sound, the effects of a hallucinogenic trip. A long sequence of body close-ups in studio environment ensues among jungle exteriors before the audience is dumped back in Mexico City, where the death of Burroughs’s wife, never used as a plot in the earlier part of the film, is referred to as a central motive.

Sure, the ending is confused, but even more so if the life story and the books have not been digested. Craig makes no attempt to mimic the voice or movements of Burroughs as caught in archive footage – instead, he relies completely on the text and the screenplay for his direction. Whatever the method and approach, the result is a picture that brings the Burroughs legend to many more people of a young and liberal disposition.

This can’t be a bad thing.

Saturday, November 2, 2024

Bngkok City of Angels - Feature Length Documentary Released.